Employers operating in Thailand can enforce post-employment noncompete covenants, but success depends on precise drafting and strong evidentiary support. Thai courts will uphold restraints that protect legitimate employer interests and are fair and reasonable in duration, geographic reach, and substantive scope. Overbroad covenants, however, draw judicial skepticism and may fail unless they are drafted in severable, defensible components tied to the employee’s actual role.

This article synthesizes recent trends in Thai case practice, explains how Thai courts assess reasonableness in employment restraints, and provides a practical litigation-focused framework for drafting enforceable covenants, preparing evidence, and pursuing relief through the Labor Court.

The Legal Framework and Its Practical Implications

Thai courts evaluate noncompete covenants under general principles of contract enforceability and public policy, with particular focus on whether a restraint is necessary to protect a legitimate employer interest and proportionate to that objective. In employment matters, this analysis is shaped by the employee-protective tenor of Thai labor law and by the Labor Court’s equitable discretion in determining appropriate remedies.

The practical takeaway is that standardized or broadly drafted covenants rarely survive scrutiny. Courts look for a demonstrable nexus between the employee’s actual exposure to confidential information, trade secrets, or customer relationships and the scope of the restraint. Where that nexus is weak or the restraint operates as a blanket prohibition, courts are inclined to decline enforcement or limit relief to a narrowly tailored prohibition.

The employer interests most commonly recognized as legitimate in Thai practice include the protection of trade secrets, confidential business information, and goodwill tied to identifiable customer segments or territories. Courts are more likely to enforce restraints where employers can clearly document what information is at risk, why particular customer relationships matter, and how the employee was involved with those assets. Judges also look closely at the employee’s seniority and level of responsibility. Where a role was largely operational and lacked strategic or commercial influence, broad territorial or activity-based restrictions are more likely to be seen as punitive rather than protective.

Public policy considerations further shape outcomes. Thai courts will not enforce restraints that unduly restrict an individual’s ability to earn a livelihood or that appear designed to deter employee mobility rather than to protect legitimate interests. The more a covenant resembles a blanket ban on working for competitors without clear linkage to the employee’s actual duties, the more likely it is to be viewed as contrary to good morals or public order.

How Thai Courts Weigh Reasonableness in Practice

In practice, judicial assessment of reasonableness turns on three core variables: duration, geographic scope, and activity scope. Duration is assessed by considering how long the employer’s confidential information retains competitive value and how long customer relationships remain vulnerable. Geographic scope is evaluated by comparing the employer’s actual area of competition with the territories where the employee exercised influence. Activity scope is measured by comparing the restricted activities to the employee’s actual responsibilities and access to sensitive information.

Evidentiary presentation often determines outcomes. Employers who can map specific categories of confidentiality information, trace client-contact histories, and support their claims with contemporaneous business plans or internal policies are better positioned to justify tailored restraints. Courts also consider whether the employer offered benefits that mitigate the burden of the restriction, such as paid garden leave or post-termination incentives tied to confidentiality or nonsolicitation obligations.

Partial enforcement remains a nuanced and fact-sensitive area. Thai courts are cautious about rewriting parties’ agreements but may be more receptive to enforcing narrower, severable provisions where the contract is drafted in modular form and the offending restriction can be cleanly excised. Clauses that separately identify protected customer lists, product lines, or business units give courts legally comfortable alternatives. Employers should not assume that a court will “fix” an overbroad clause; therefore, drafting with severability in mind is essential.

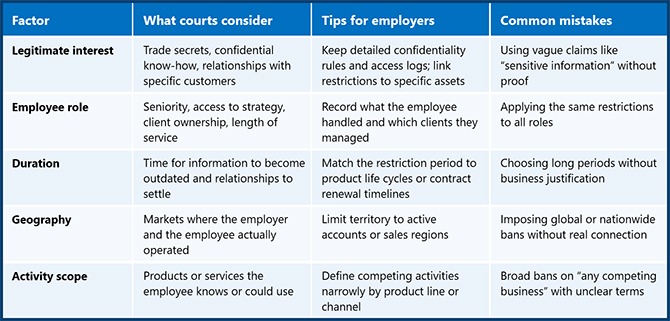

The table below outlines several reasonableness factors commonly considered by Thai courts, along with some practical considerations for Thai noncompete disputes. This is a general summary of Thai court trends; actual outcomes depend on facts, evidence, and judicial discretion.

Drafting Covenants That Survive Scrutiny

Effective noncompete drafting in Thailand is role-specific and evidence-driven. Precision begins with clearly identifying a legitimate interest at risk, such as clearly labeled trade secrets or a defined list of key customers for whom the employee had primary responsibility during a specified look-back period. Noncompete clauses should be paired with robust confidentiality and nonsolicitation clauses, each drafted with distinct elements and express severability language so that a court can enforce what is necessary without endorsing an overinclusive restraint.

Territorial scope should be articulated by reference to where the employee will actually work and where the employer holds a demonstrable competitive presence that the employee could realistically harm. Duration should likewise be justifiable on its face. Where a restraint corresponds to customer renewal cycles, sales seasons, or product development timelines, courts are more likely to view it as proportionate. Employers can further strengthen perceived fairness by offering benefits that soften the restriction, such as paid garden leave during notice periods or tailored post-termination compensation. While these measures do not guarantee enforcement, they reinforce proportionality and good faith.

Drafting should also account for dispute resolution realities. Employment disputes in Thailand fall within the jurisdiction of the Labor Court, and contracts should be designed to function effectively in that forum. Arbitration clauses may raise enforceability or public policy concerns depending on the circumstances. Where arbitration is contemplated for senior executives, agreements should preserve access to court relief, particularly for the protection of trade secrets or customer relationships at the early stages of a dispute.

Cross-Border Mobility and Multi-Jurisdiction Dynamics

Multinational employers operating in Thailand must anticipate employee moves across Southeast Asia and beyond. While Thai courts assess the enforceability of noncompete obligations independently under Thai law, they may consider foreign judgments or arbitral awards as persuasive background without being bound by them. That limited deference underscores the need for forward-looking coordination at the drafting and enforcement stages. Employers should aim for conceptual consistency across jurisdictions where feasible, but they should not assume that provisions permissible elsewhere, such as punitive liquidated damages (which are disfavored under Thai law), will be acceptable in Thailand. Similar care is required at the evidentiary stage. Evidence generation must account for cross-border data protection constraints. When gathering and sharing evidence with foreign counsel or courts, employers should structure personal data handling to comply with Thailand’s Personal Data Protection Act while preserving the integrity of the evidentiary record.

Related considerations arise in the selection of governing law and dispute forums. Choice-of-law and forum-selection clauses require careful thought for regional executives whose responsibilities span multiple countries. Thai courts scrutinize such clauses in employment agreements and will not enforce them to the extent they contravene Thai public policy or deprive employees of legal or statutory protections. Employers should therefore model dispute scenarios for key executive roles and select clauses that preserve access to relief in Thailand even when foreign law or foreign-seated arbitration features elsewhere in the contract.

Remedies, Damages, and Compliance Programs

Damages in noncompete litigation are highly fact-specific and turn on proof of loss or unjust enrichment, which can be challenging to quantify. This reality underscores the importance of negotiated solutions. While contractual liquidated damages can serve as a useful benchmark, they must reflect a genuine pre-estimate of loss to avoid being treated as an unenforceable penalty. Even where penalties are specified, Thai courts retain discretion to reduce excessive amounts. Against this backdrop, employers should maintain calibrated compliance programs to reduce litigation risk. Structured exit processes, return-of-information protocols, and written acknowledgments of continuing obligations at departure all help limit disputes and strengthen enforcement positions.

Long-term enforceability is best supported by compliance programs that reduce reliance on broad post-employment restraints. Measures such as segregating sensitive information, tracking access rights, documenting client ownership, and implementing structured exit protocols both limit the scope of potential disputes and strengthen evidentiary positioning. When disputes do arise, these systems provide the records courts expect and improve settlement leverage, particularly when an employer can credibly demonstrate readiness to litigate based on a coherent, well-documented record.

Conclusion

Thai courts are willing to enforce post-employment noncompete covenants that protect legitimate employer interests through narrowly tailored restraints tied to an employee’s actual role, access, and exposure. Employers who draft with precision, severability, and proportionality in mind and who generate evidence linking restraints to identifiable assets, relationships, and risks are best positioned to obtain commercially sustainable settlements. While uncertainty persists at the margins, particularly regarding acceptable duration and the scope of partial enforcement, conservative drafting, disciplined documentation, and alignment with Labor Court expectations remain the most effective risk-management tools in an increasingly mobile and cross-border employment market.